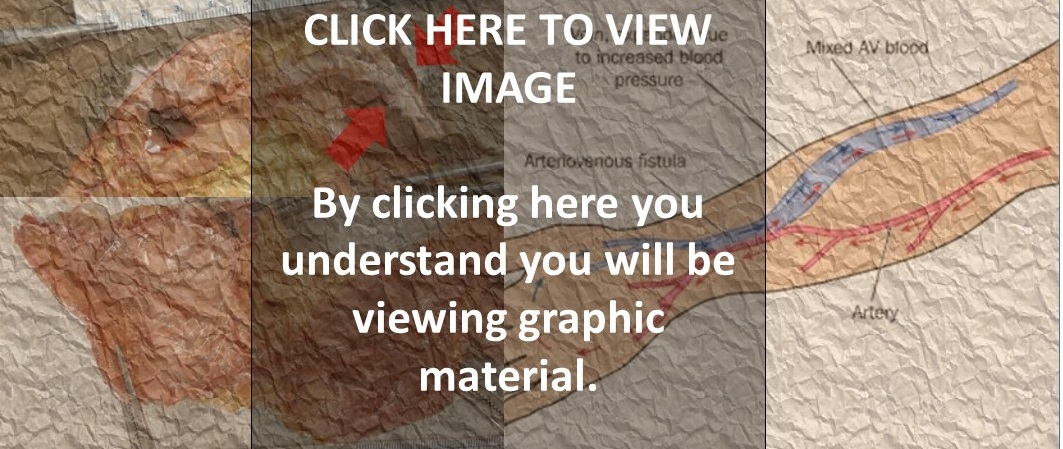

What is shown?

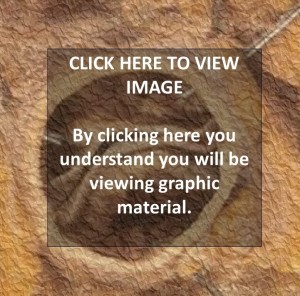

The upper left photograph shows a dissection of an arm. The AV fistula is visible below the skin. The upper arrow shows how paper thin the skin is right next to the AV fistula. The lower arrow shows how paper thin the AV fistula itself is.

The bottom left photographs shows the AV fistula removed from the arm. Each attached clamp holds an expanded portion of the AV fistula. The connection in between is less expanded. The yellow tissue is attached fat.

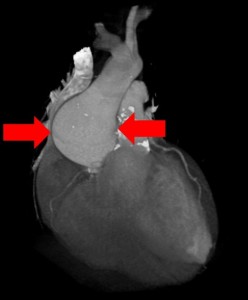

The right image shows a diagram of an AV fistula.

What is an AV fistula?

The “A” in AV fistula stands for “arterio” (relating to arteries – the high pressure blood vessels carrying blood away from the heart). The “V” in AV fistula stands for “venous” (relating to veins – the low pressure blood vessels returning blood to the heart). A fistula, in this case, means a surgically created connection. So an AV fistula is a surgically created connection between an artery and a vein. It stands for arteriovenous fistula.

Why did this patient have an AV fistula?

AV fistulas are created by surgeons to help patients who need dialysis. To have dialysis, large needles need to access the blood stream. An AV fistula provides a large vein to allow for this kind of access.

How do AV fistulas provide large veins?

Veins are normally used to the low pressure blood flow inside them. If a vein is surgically connected directly to an artery (under higher pressure), the vein swells and expands under the pressure from the artery. The vein becomes big enough to be used for dialyis. This swollen vein is illustrated in the image on the right.

What was the story here?

In this case, an elderly man needed dialysis for his kidney disease. He had an AV fistula placed. The fistula worked for many years. One month before he died, his fistula began to leak. The first time was at home. He woke up to find his bed sheets soaked in blood. He went to the hospital, received blood transfusions and was sent home. A couple weeks later, he bled again, also at home. A third time occurred during dialysis, requiring his arm to be tournequetted while the bleeding was stopped. He was sent home again. The following week, he was found in the bathroom having bled to death from his arm.

Why did the family request an autopsy?

They wanted to know more information about why the AV fistula leaked. In addition, the family wondered why their loved one, after several bleeding episodes, did not receive any specific plan to prevent further bleeding (for example creating and using a new dialysis access site). It seemed that the only medical care was to replace lost blood, but that the AV fistula continued to be used. They were looking for more information to understand what had happened.

What did the autopsy show?

The autopsy showed why the AV fistula had become at risk for rupture and bleeding. The photographs show how thin the skin was over the AV fistula, how thin the AV fistula was itself and how close the two were. After multiple punctures, the two had scarred together, thinned and become brittle. This explained how the fistula was at risk for rupture and bleeding.

How did the autopsy help?

Despite the clear clinical history of bleeding from the arm, it was not clear to the family what had happened. They imagined that the fistula itself was full of many, many holes (from “too many” needle sticks). Instead, the autopsy showed that most of the AV fistula was normally formed; and that the problem was right at the surface where the skin had thinned and become brittle over the years. This provided a clearer, less “dramatic” (and, therefore, less stressful) picture for the family.

In addition, the discussion allowed for a validation of the family’s concern about continued use of an AV fistula that had ruptured three times. For an AV fistula that had worked for many years to rupture more than once, there would be no reason to think the bleeding wouldn’t happen again. Unfortunately in this case, the patient died as a result. Talking it through with a clear understanding of the findings helped the family come to terms with events surrounding the loss of their loved one.

You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.

You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.