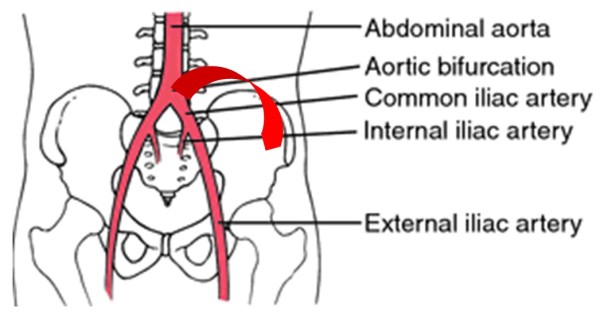

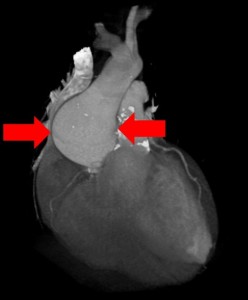

What is shown?

The top image shows the heart sac opened in the chest. The sac is full of blood (cardiac tamponade). The bottom image shows the heart after the blood around it has been removed. The view is of the back of the heart. There is a T-shaped hemorrhage. The right coronary artery (RCA) wraps around from the front and is seen on the top right. The left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) also wraps around from the front and is seen the top left. The posterior descending coronary artery (PDA) branches off the RCA and travels down the middle of the back of the heart.

What was the story here?

The patient was a middle aged man who came in to the hospital short of breath for several days after getting through a cold. He had a coronary artery stent put in his right coronary artery. The procedure seemed to go well. Later in the afternoon, he became dizzy, collapsed and died. His wife spoke with the cardiologist who explained it was probably a “stroke.” The wife could not understand why, suddenly, there was a stroke right after the procedure. She also didn’t believe he had any blockages because the husband had been athletic. She requested an autopsy and retained a lawyer.

What caused the blood on the back of the heart?

The blood on the surface of the back of the heart tracks along the coronary arteries. (The coronary arteries travel over the surface of the heart). This suggests the blood came from the coronary artery itself. Because a stent was placed in the same area as the hemorrhage, this suggests that a coronary artery ruptured related to the placement of the stent. Other possibilities would be a CPR-related contusion (but that would not track along blood vessels); or a tear of the muscle heart muscle wall (but that did not happen either).

How did the person die?

After the vessel ruptured, the blood also leaked into the sac around the heart. When the heart sac fills with blood, there is no room for the heart to beat. The heart is squeezed by the blood in the sac. This can cause the patient to collapse and die. This is what happened here.

Could the rupture have happened on its own, unrelated to the procedure?

No. Spontaneous rupture of coronary arteries is documented but extremely rare. The rupture was right in the region where the stent was placed and indicated the procedure had a role in the rupture.

What else did the autopsy show?

The autopsy showed very little coronary blockage overall and a viral infection of the heart muscle (viral myocarditis).

How did the autopsy help?

The autopsy helped on a variety of levels. It determined the cause of death (coronary rupture with tamponade). It also provided information on the prior health of the heart (viral myocarditis). The patient’s shortness of breath was likely from his heart infection; and his heart infection was likely a complication from his recent viral illness (“cold”). The results also shed light on the role of the procedure in the patient’s death. Because the patient’s coronary arteries were “open,” the procedure was unnecessary. Moreover, it caused his death.

What was the impact of the autopsy results on the family’s emotions?

Difficult as the information was to consider that the death was intimately related to the care, the information from the autopsy helped the family move on from the painful restlessness of “not knowing.” At the same time the results deepened the wife’s concern regarding the cardiologist’s explanation and behavior. She began to suspect that her husband had been left to die at the time of the code (because the cardiologist did not seem to consider a diagnosis related to the heart). On top of this, she felt profoundly dismissed that there seemed to be no consideration that her husband’s death may have had any connection to a procedure hours before — a “common sense” consideration given the time frame. The autopsy results validated her concerns. Before the autopsy, the wife was left not knowing what had happened with the cardiologist telling her it was a stroke. After the autopsy, the wife knew what happened, which diminished her dependence on the cardiologist and seemed to have a liberating effect.

Why would the cardiologist suggest the cause of death was a stroke?

The cardiologist’s comments are filtered through the wife and we can’t really know what he said. If the report is accurate, it is concerning. Was this “physician hubris” (“My procedure can’t have caused a problem. I know I did everything right!”)? Was he being dismissiveness of the wife’s intelligence? Was this fear of a medical error being discovered and an attempt to deflect the wife from the “truth”? Was he really suspicious of a stroke on clinical grounds? Which option, or some other, cannot be ascertained here. But, the possibility that truth dismissed caused the patient’s death (by inattention to a procedural complication during the code) is horrific.

Summary Comment:

The issues in this case are multiple. They include a missed initial diagnosis (myocarditis); an erroneous assessment of coronary blockages (open and not blocked); a procedural complication (coronary artery rupture related to stent placement); and, possibly, misdiagnosis of stroke during the patient’s code. Probably least in question here is the actual technique of placement of the stent — the reason being that the coronary artery wall into which the stent was placed was not firm with plaque, but a pliable normal vessel. It was possibly more easily damaged by a metal stent than one shored up by at least some firm cholesterol plaque. While seemingly remote, there is a possibility that standard of care was met at various points. It would take a review of the presenting data, angiograms, the operative note, the post-operative care, and so on. However, the autopsy served to secure the truth — of benefit to the clinicians and to the wife sorely in need of information.

You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.

You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.