You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.

You perform an autopsy on an elderly man who died suddenly at home. The gentleman was stoic, somewhat distant from his family and never sought medical care. There are four adult children who call you to perform an autopsy. They would like to know what happened.

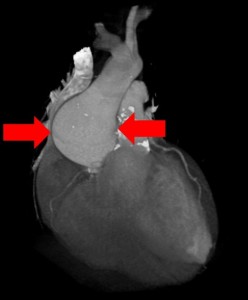

During the autopsy, you find that the sac around the heart is full of blood. Your first thought is to consider either a heart attack with rupture of the heart muscle; or an aortic aneurysm with rupture of the aorta.

The coronary arteries are whistle clean (no significant blockage by plaque) and the heart muscle is healthy. There was no heart attack. But the aorta coming out of the heart is twice as wide as normal and there’s a half-inch tear in it close to the heart. It’s the aorta that has ruptured.

You consider high blood pressure as a common cause of aortic aneurysm. But if there were many years of high blood pressure, the heart should be bigger than normal and the kidneys should have a rough surface. The heart is normal size and the kidneys are smooth. It doesn’t look like there was high blood pressure.

You wonder about the inherited condition, Marfan syndrome, which goes along with a stretched out aorta and aortic rupture. But patients with Marfan syndrome tend to be tall and this gentleman is short. Marfan syndrome is unlikely.

You continue a systematic assessment of the heart, continuing with the heart valves. First you assess the valves on the right side of the heart: Tricuspid valve. “One, two, three leaflets. All thin and pliable. No problem there,” you think. Now the pulmonic valve. “One, two, three leaflets. All thin and pliable. No problem there.” You move on to the left side of the heart, looking at the mitral valve. “One, two leaflets, no problems.” Then you look the aortic valve, “One, two….”

Suddenly you realize you better call the family in. The autopsy results may save their lives.

What did you see?

35 thoughts on “Sleuth It — What Counts in the Heart?”